Updated 04-02-2024

I recently had a very interesting case in which the client was diagnosed with plantar fasciitis, but the traditional treatment for it did not work. In fact, the often prescribed orthotics and switch to high-arch footwear made the condition worse. To me, the initial client description in her history sounded more like nerve pain and less like the typical presentation of plantar fasciitis. Digging deeper revealed some interesting pieces of the puzzle. Pain on the bottom of the foot can be debilitating and sometimes persist for several years. The most common cause of plantar foot pain is plantar fasciitis, often diagnosed when pain on the underside of the foot is aggravated by activity. However, in some cases, this pain may persist despite attempted treatment and not responding to the typical treatments for plantar fasciitis. When standard therapies are unsuccessful, the primary problem may not be with the plantar fascia.

Baxter’s neuropathy is a condition in which the dysfunction is not with the plantar fascia but with deeper tissues in the mid-arch of the foot. This nerve impingement involves the inferior calcaneal nerve (ICN) under the arch of the foot. The ICN is a lateral plantar nerve branch on the foot’s bottom surface, sometimes called Baxter’s nerve. It was named after the first physician who described this nerve compression as a specific cause of foot pain. Baxter’s neuropathy may account for up to 20% of heel pain cases (2,3). It’s symptoms can be similar to, but not exactly that of plantar fasciitis, making taking a decent history very important.

Location and Structure

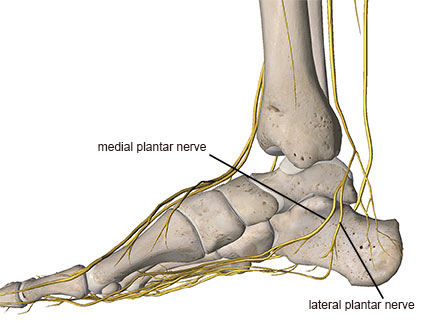

The tibial nerve divides into two primary branches, the medial and lateral plantar nerves, as it passes around the medial side of the ankle in the tarsal tunnel (Figure 1). Both branches curve around the medial ankle and course along the foot’s bottom surface.

Figure 1

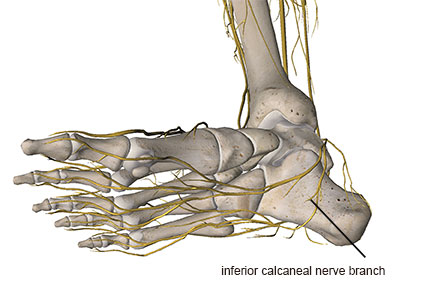

The inferior calcaneal nerve (ICN) is the first smaller branch that splits from the lateral plantar nerve (Figure 2). In most people, the ICN branch splits off from the lateral plantar nerve on the underside of the foot. However, in some cases, the ICN may branch off more proximally, even as far up as the tarsal tunnel on the medial ankle.

Figure 2

The location and manner in which nerve branches are clinically relevant because nerve branching can increase tensile or compressive loads on the nerve, potentially leading to nerve injury.(1) Another factor that makes the plantar nerves and their branches more susceptible to injury and irritation is the sharp right-angle turn from the medial side of the foot to the plantar surface.

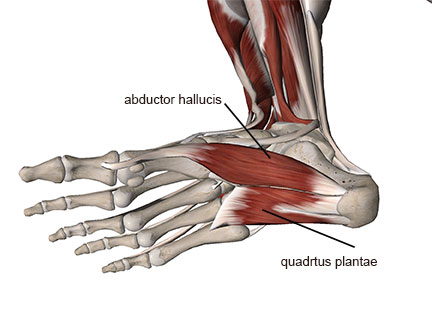

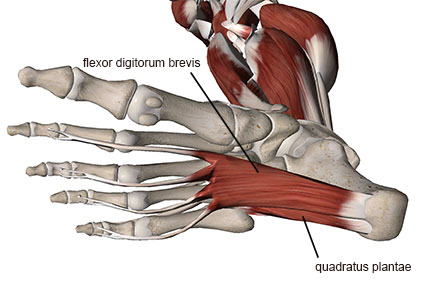

In Baxter’s neuropathy, there are two potential locations where the ICN can become entrapped. The first is between the deep fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle and the quadratus plantae muscle (Figure 3).

Figure 3

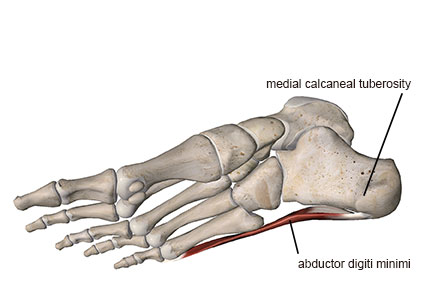

The second is along the medial calcaneal tuberosity, where the nerve can be compressed against the bone or bone spurs that may have developed along the anterior calcaneus (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Bone spurs at the front of the heel bone (calcaneus) are thought to result from tensile forces on the attachment sites of the toe flexor muscles or the plantar fascia. While bone spurs are often described as a primary cause of heel or foot pain, recent theories suggest that they may result from specific biomechanical forces in the foot but are not necessarily the leading cause of foot pain.

Since spurs occur on the front of the calcaneus, it is unlikely that there is direct pressure from weight-bearing on the spur. Moreover, spurs can occur in other parts of the body without causing pain. Compression of the inferior calcaneal nerve (ICN) may be the primary cause of pain in cases where bone spurs are present. The spur can project into the path of the ICN, causing increased nerve compression.

Assessment

Baxter’s neuropathy is not frequently described in the orthopedic literature, suggesting it may be misdiagnosed. If misdiagnosed as another common condition, such as plantar fasciitis, traditional treatments could be ineffective or worsen the condition. Treatment approaches for plantar fasciitis vary widely, so it’s important to consider the possibility of ICN compression in any long-term complaint, especially if it does not respond to traditional treatment.

The ICN is a mixed motor and sensory nerve, so nerve compression may cause pain in the foot or ankle and muscle atrophy if the motor fibers are affected. The abductor digiti minimi (ADM) muscle is most commonly affected when motor fibers are involved, although the ICN may also innervate the flexor digitorum brevis and the quadratus plantae muscles in some cases (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Identifying compression of the inferior calcaneal nerve through physical examination can be challenging. However, a few methods may help determine the possibility of this nerve’s involvement. Pain is usually present when palpating along the arch on the bottom surface of the foot. In some cases, pain with palpation may be more pronounced along the lateral aspect of the plantar surface, where the abductor digiti minimi (ADM) muscle is located. Pain may also be elicited by palpating along the medial arch, where the nerve is likely to be entrapped.

The inferior calcaneal nerve does not always innervate the flexor digitorum brevis muscle. Still, when it is, there may be a weakness in this muscle that is apparent when resisting flexion of the last four toes. One way to examine this is to place a thick card, like a business card or standard 3×5 index card, on the ground. Ask the client to hold the card down with all four toes while attempting to pull it out slowly (Figure 6). If they cannot hold the card, or if it appears easier to pull the card away compared to performing the same procedure on the other side, there is likely weakness in the flexor digitorum brevis muscle. This may indicate potential compression of the inferior calcaneal nerve.

Figure 6

One of the more accurate methods of determining the involvement of this small nerve is an MRI.(4) When motor fibers to the ADM muscle are damaged, the muscle will atrophy, and fatty edema can build up. This fatty infiltration is visible on the MRI. Because it is so difficult to identify the clinical indicators of inferior calcaneal nerve compression through physical examination, this nerve compression pathology is often missed if an MRI is not performed.

Baxter’s neuropathy is likely to occur in conjunction with other foot pain problems, making its presence more challenging to identify. One study found a strong correlation between ICN compression and three other key factors: increased age, calcaneal bone spurs, and plantar fasciitis.2 It may also result from specific biomechanical challenges in the foot, such as pes planus (flat foot).(4)

Treatment Strategies

As with all nerve compression problems, it is important not to exaggerate nerve irritation during treatment, as this could worsen the condition. Communicate closely with your client as you work to ensure symptoms aren’t significantly increased as you use these or other treatments.

Since nerve compression can occur between soft tissues (the deep fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle and the quadratus plantae muscle), massage could help reduce compressive forces on the nerve. Soft tissue treatment may also reduce nerve irritability by reducing tensile forces pulling on the nerve.

Tensile or compressive forces on the nerve can increase nerve pain in many cases. These forces may be relatively small but can still produce detrimental results. Moving soft tissues in a direction that relieves stress on the nerve is often very helpful. It allows the brain to reset its perceived noxious input from pain receptors, decreasing pain. Knowing your anatomy is critical to finding the appropriate direction to move the foot, which can also vary to some degree from person to person.

The massage therapist can help by moving the foot in particular directions to relieve tension. The first way to do this is to move the foot into inversion. The effectiveness of this treatment will be known when the direction of movement relieves tensile loading on the nerve and reduces pain. Experiment with your client to find the most comfortable position.

The second way to relieve nerve tension is to grasp the heel and hindfoot and gently pull them in a medial direction (Figure 7). Ask the client if the position or movement reduces any of the foot pain. The ADM muscle or arch of the foot may be painful with palpation. Pressing on one of these sore areas as you perform the heel/foot movements may be helpful. Look for reduced pain when this technique is applied.

Figure 7

Once you find a position that decreases pain, hold it for about two minutes and slowly and gradually release it. After releasing the hold, perform very gentle and easy passive movements with the foot to help encourage freedom of movement and to reestablish new, reduced levels of neural reporting. The more frequently this technique is applied, the more beneficial it will be. Teaching the client how to do this at home can be helpful, as compliance is vital to successful treatment.

As a massage therapist, you will likely continue encountering clients complaining of plantar foot pain. If traditional strategies are unsuccessful, consider other possibilities, such as ICN compression. Many people have to live with significant pain for a long time without anyone considering alternative causes. If you are a healthcare professional who looks outside the box to help them find relief, you will be forever appreciated, as this condition can be disabling.

Notes:

- Butler D. Mobilisation of the Nervous System. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1991.

- Chundru U, Liebeskind A, Seidelmann F, Fogel J, Franklin P, Beltran J. Plantar fasciitis and calcaneal spur formation are associated with abductor digiti minimi atrophy on MRI of the foot. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(6):505-510.

- Pecina M, Markiewitz A, Krmpotic-Nemanic J. Tunnel Syndromes: Peripheral Nerve Compression Syndromes. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2001.

- Dirim B, Resnick D, Ozenler NK. Bilateral Baxter’s neuropathy secondary to plantar fasciitis. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16(4):CS50-CS53.