Research Review: Conservative Treatment of a SLAP lesion

- Whitney Lowe

Blanchette M-A, Pham A-T, Grenier J-M. Conservative treatment of a rock climber with a SLAP lesion: a case report. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2015;59(3):238-244.

Introduction

This is a case report of conservative management of an injury to the glenoid labrum, called a SLAP lesion. Usually this condition is a surgical problem, but this single case study suggests that conservative management is possible. The case involves an individual who had an acute injury during a rock climbing incident. Initially conservative treatment was tried and it was unsuccessful. The individual was going to pursue surgical treatment but tried one more round of conservative therapy with the authors of the paper and found it to be successful in alleviating the complaint.

What do you think about this treatment and case?

Anatomical Background

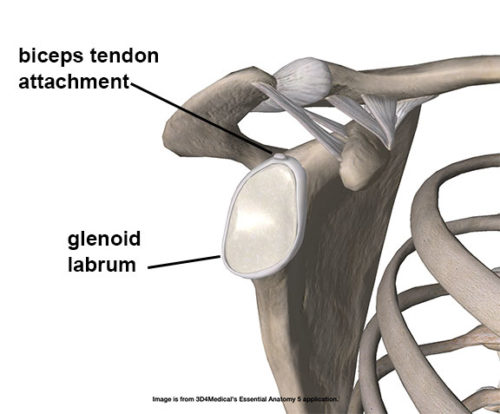

The glenoid fossa is a very shallow depression on the scapula. In order to increase stability at the glenohumeral joint the fossa is surrounded by a rim of cartilage called the glenoid labrum (Figure 1). The primary function of the labrum is too deepen the socket for the glenohumeral joint and therefore provide greater stability.

Figure 1: The glenoid labrum and biceps tendon attachment

The labrum also has attachment to numerous soft tissues around the shoulder joint. Glenohumeral ligaments as well as the joint capsule attach around the periphery of the labrum. The tendon from the long head of the biceps brachii also attaches to the superior portion of the labrum and that is the region affected in this particular condition.

Most anatomy texts list the supraglenoid tubercle as the attachment site for the long head of the biceps brachii. However, the authors cite a cadaver study that showed 50% of the biceps tendon fibers attaching to the labrum, and 50% to the supraglenoid tubercle. Consequently there are significant tensile loads transmitted to the glenoid labrum from strong contractions of the biceps brachii.

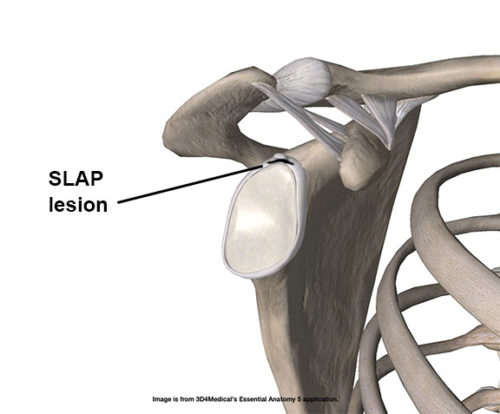

The injury discussed in this clinical case is called a SLAP lesion. The term SLAP is an acronym for Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior, indicating a tear in the superior portion of the labrum that goes in an anterior to posterior direction (Figure 2). Note that the biceps tendon attaches right over the superior portion of the labrum, so extreme tensile forces from this tendon can pull on the labrum strong enough to tear it away from its attachment site and cause the SLAP lesion.

Figure 2: Location of the SLAP lesion on the superior labrum

SLAP lesions are more common with those who are young and active. It is especially common in those involved in vigorous throwing activities. As with other similar soft-tissue injuries, it can take a long time to heal because the blood supply to the superior portion of the labrum is poor compared to other tissues.

SLAP Lesions: General

The SLAP lesion often presents with a sudden onset injury accompanied by a popping or snapping sensation. There may be pain at the time of injury, but it may decrease immediately after the injury. Often the shoulder will not be painful during certain movements, but very painful during others.

This case describes a rock climber who had the shoulder in a significantly abducted and externally rotated position when the injury occurred. This particular position of the shoulder does not necessarily stress the biceps tendon long head attachment on the labrum. But if his arm was in this position as he was attempting to hold his body weight, the biceps is at a mechanical disadvantage holding a strong load and that could be what induced the injury.

SLAP lesions often occur with sudden traction of the arm or forceful contraction of the biceps. Rotator cuff tears that disturb glenohumeral mechanics are also a likely cause. Another common cause of SLAP lesions is falling on an outstretched hand (also called a FOOSH injury). Falling and hitting the ground with the arm outstretched causes the humeral head to be driven in a posterior or superior direction and may tear the superior labrum in the process.

SLAP lesions are very difficult to identify through physical examination alone because it is difficult to palpate or stress the labrum with physical examination methods. Detailed high-tech diagnostic imaging such as MRI is usually required to confirm their presence. There are other corresponding factors that may be present during physical examination. The authors in this clinical study reported finding trigger points in the supraspinatus, subscapularis, infraspinatus, teres minor, biceps long head, rhomboids, and serratus anterior.

During evaluation SLAP lesions commonly show a pattern of altered shoulder rotation. The easiest way to see these altered patterns is to have the client in a supine position. Internal and external rotation of the shoulder are evaluated from the supine position. When a SLAP lesion is present it is common to see an increase of external rotation and a decrease of internal rotation.

There are number of special orthopedic tests that have been developed to examine for the presence of the SLAP lesion. Unfortunately despite some initial encouragement about their use, most of them have not proven very accurate in identifying the presence of SLAP lesions.

Treatment

In this clinical study, the individual had started with conservative therapy and found it to be ineffective. He had scheduled surgery for the problem but decided to go one more round of conservative therapy with different practitioners using a different approach. Initial conservative treatment was performed by a chiropractor and was not successful. It had consisted of transverse friction at the insertion of the rotator cuff tendons and spinal manipulative therapy of the thoracic spine.

The second round of conservative treatment, which was performed by the authors of this case report, included soft-tissue mobilization techniques such as Active Release® and Graston® methods. They also employed strengthening exercises for scapular stabilizer muscles. After four treatments the patient canceled a planned surgical procedure because he said the shoulder was pain free.

The authors did not give specifics about exactly what was done in each treatment session so it is difficult to determine how these various treatment approaches actually contributed to the relief of symptoms.

Discussion

The authors state that having tried other conservative approaches it’s likely that manual therapy including the Active Release® and Graston® methods along with scapular stabilization was instrumental in alleviating this complaint.

Active Release is a patented version of active engagement techniques which have been used in sports massage for decades. Graston is another patented version of a common soft-tissue treatment called Gua Sha, which is a traditional Chinese medicine treatment with a very long history.

The authors describe the scapular stabilization methods used as one or two simple exercises, “Strengthening exercises of the external shoulder rotator (with an elastic band) and the serratus anterior (scapular “push up”).

The authors do not describe the actual physiology of the interventions or the physiological goals they are seeking with these modalities. There is no discussion as to why a soft tissue treatment method aimed at the superficial tissues of the shoulder (Graston or Gua Sha) helped alleviate the pain and dysfunction of a labral tear.

Because none of the described treatment approaches specifically targeted the glenoid labrum, we are left to consider that the results might be from indirect tissue effects and not something directly applied to the labrum. That is not necessarily bad. However it might be a little misleading with this case study simply suggesting that these particular patented treatment techniques can resolve labral injuries.

The authors do not describe the actual physiology of the interventions or the physiological goals they are seeking with these modalities. There is no discussion as to why a soft tissue treatment method aimed at the superficial tissues of the shoulder (Graston or Gua Sha) helped alleviate the pain and dysfunction of a labral tear.

As a result, the reader is left with a study that amounts to a circumstantial resolution of a labral tear. There are several things that could be happening in the relief of pain for their client. First, is that the tear could have been small enough to be repaired with scar tissue. Scar tissue is the primary way in which the body repairs all soft-tissues. Since there is no reference to tear size or MRI reports, we cannot know the severity of the tear. In many cases, shoulder and other ligament injuries are resolved through conservative measures, such as physical therapy, without surgery. This study alone does nothing to support the use of patented techniques as Graston or Active Release.

Additionally, without a follow-up MRI to show the end-treatment condition of the labral tear, we cannot know the condition of the tear or if the treatments did anything to resolve the actual tear. The authors also do not mention how long they followed their patient after treatment.

It is common for manual therapy interventions to make positive effects in pain reduction even in the presence of tissue damage that still exists. Descending modulation or inhibition of neural signals is often credited with these results. It is entirely possible that the results of this case study had little to do with the impact of manual therapy intervention on the labrum, and more to do with some of these other peripheral effects. This possibility should have been addressed in their discussion.

In Sum

Keep in mind that this is a single case study and the results cannot necessarily be generalized to other situations. There are many situations where a treatment regimen is described and positive outcomes resulted. However in many situations the physiological mechanism by which the treatment worked is not described, making it hard to extrapolate these findings to other similar situations.

Conservative, non-surgical, treatment is always preferable if those treatments are effective and successful in actually resolving a complaint. However, studies that seek to document such treatment should be stringent and specific enough to document all aspects of the process. Anecdotal accounts of recovery, while encouraging to clients, do not produce results that can be readily reproduced by others investigating a similar or the same injury/condition. The sign of sound science is can the study and results be reproduced?

It is always wise to try a round of conservative approaches – massage, physical therapy, or rest from offending activities. In the end though, surgery may be the only resolution to tissue repair. If resolution, proven with applicable assessment protocols (whether technological or functional), does not come then referral to other healthcare providers is a wise choice.