Research Review: Neuroplasticity in the Central Nervous System

- Whitney Lowe

Research Review:

Pelletier R, Higgins J, Bourbonnais D. Is neuroplasticity in the central nervous system the missing link to our understanding of chronic musculoskeletal disorders? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(1):25.

The treatment of musculoskeletal disorders has historically focused on a structural-pathology paradigm where the primary source of dysfunction (and consequently pain) is caused by some local site of tissue injury. However, this paradigm falls short in many chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions where a distinct tissue pathology cannot be identified. In many cases diagnostic findings correlate poorly with levels of reported pain and dysfunction.

Some of the key problems people have are:

- damaged musculoskeletal structures that are asymptomatic,

- symptoms without damage to specific structures

- bilateral pain problems with unilateral tissue damage

- some people heal while others develop chronic musculoskeletal disorders

- persistent sensorimotor dysfunction associated with many conditions

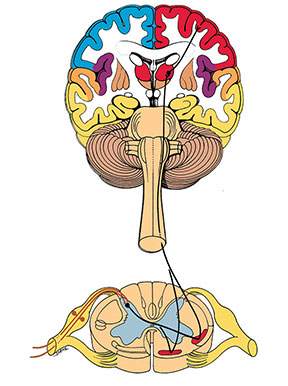

The authors state that “Neuroplasticity is an intrinsic fundamental neuro- physiological feature that refers to changes in structure, function and organization within the nervous system that occurs continuously throughout a person’s lifetime”2 Neuroplasticity is a hot topic in medical research as scientists have discovered that the brain is capable of great adaptation and can continue to create new neural connections regardless of age. The brain is also capable of making significant new connections in response to injury or trauma such as those that re-learn activities after stroke or other peripheral limb injuries.

Neurophysiological changes directed by the brain occur after an injury as a protective strategy. Essentially the brain is altering how the body responds in the injury area to protect it from further damage. However, it appears that these changes themselves alter pain reporting processes and become part of the chronic pain pattern in long-term musculoskeletal disorders. These dysfunctional changes may persist even in the absence of true structural tissue damage. These findings have significant ramifications for the dominant structural tissue damage model used in rehabilitative treatment.

If neuroplastic changes are the primary cause of conditions moving from acute to chronic long-term stages, then treatment interventions aimed at these effects (and at central processing rather than peripheral tissue damage) may have the greatest potential success.

These findings have significant implications for how massage might be used in chronic long-term pain complaints. Researchers have found approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy, meditation, mindfulness therapy, and other stress reduction approaches very beneficial in altering dysfunction and irritability in sensory and motor pathways.

While massage was not specifically mentioned in this paper, it can be highly effective in addressing sensorimotor disturbance. Consequently there are significant implications for the role massage can play in addressing chronic musculoskeletal disorders where dysfunctional neural processing has become a key facet of the disorder. Future studies should focus on measuring and evaluating ways in which massage can most effectively contribute to positive therapeutic outcomes in these situations.

While it is disconcerting to be told that your pain is all in your head, perhaps neurophysiological changes in the brain might be playing a bigger part than previously thought.