An Inside Look at Labral Tears

- Whitney Lowe

An explanation of labral tears, the mechanisms and complications involved, and how to decide if massage would be beneficial to incorporate in treatment.

Introduction

There are many instances in the clinic in which a common clinical situation requires practitioners understand an orthopedic pathology in order to determine if massage would be an appropriate treatment. Justin’s labral tear is a perfect example of why knowing about orthopedic conditions is highly beneficial in your practice.

Justin is an active, athletic 35 year old veterinarian. One of his favorite summer sports is waterskiing. Three weeks ago he had a good fall while out jumping wakes. His ski caught the ridge of the wake as he crossed over it. He maintained his balance, but his right arm was jerked pretty hard to the right. At the time, he felt a sharp pain in his shoulder, and it has continued to bother him since.

In our interview, Justin mentioned that he had seen a physician and was told he had a labral tear. He was still a little unclear about what this was, but wondered if massage would be helpful.

So what is a labral tear?

Anatomical Background

The shoulder has the greatest range of motion of any joint in the human body. However, in order to allow for such great range of motion, there is a trade-off of stability. In fact, the human shoulder joint is one of the most unstable joints in the animal kingdom.1

The glenohumeral joint is categorized as a ball and socket joint. The humeral head is a well-rounded ball, but the glenoid fossa is not much of a socket because it is so shallow. The labrum helps make the depression deeper and aids in stability. The fossa is surrounded by a rim of cartilage called the glenoid labrum. The fibrocartilage that makes up the glenoid labrum is similar to that of the meniscus in the knee. It can be torn, chipped, or cracked, and blood supply is generally poor so it often takes a long time to heal when injured.

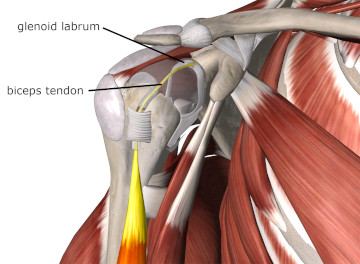

The glenoid labrum is fibrously connected to the glenoid fossa, but is also attached to other structures in the shoulder region and these other connections play an important role in many labral injuries. Along the superior margin of the shoulder joint, the tendon from the long head of the biceps brachii attaches to the supraglenoid tubercle. Prior to inserting into the bone, the biceps brachii blends fibrously into the superior portion of the labrum (Figure 1). This connection plays a very important role in labral tears like the one Justin experienced.

Figure 1

Humeral head cut away to show biceps tendon blending into superior labrum

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 5 application

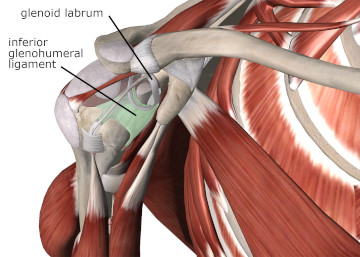

In addition to the biceps tendon, a number of ligaments that comprise the glenohumeral joint capsule also attach around the rim of the glenoid labrum. Of particular interest is the inferior glenohumeral ligament as it is commonly involved in labral injuries (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Humeral head cut away to show inferior glenohumeral ligament and lower labral attachment

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 5 application

Mechanism of Labral Injury

There are two common types of injuries that occur to the glenoid labrum. The first involves the biceps tendon attachment along the upper margin of the labrum. We’ll take a look at that one first. Then we’ll take a look at the other region of labral injury which is the anterior and inferior portion of the labrum.

The biceps tendon attaches directly to the labrum before it inserts into the bone. As a result, very high tensile loads generated by the biceps brachii muscle are transmitted to the upper margin of the labrum. The mechanics of Justin’s injury, as he explained it in his history, was that he was skiing behind a boat, and moving across the wake, trying to jump it. He was jerked very hard as he hit the boat’s wake. This sudden tensile load is likely what caused the labral injury he experienced.

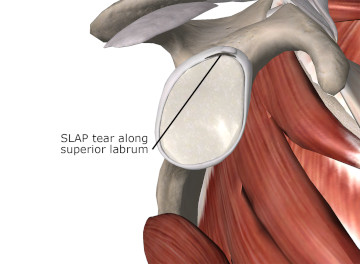

When the biceps tendon experiences an immediate, strong pull, it lifts the outer rim of the labrum and can tear it away from the more central portion. These forces will cause a tear in the superior portion of the labrum that runs from anterior to posterior (Figure 3). This particular injury is frequently referred to as a SLAP lesion. SLAP stands for Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior (meaning the tear is in the superior portion of the labrum and running from anterior to posterior).

Figure 3

Inside view of the glenohumeral joint showing a SLAP lesion along the superior labrum

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 5 application

Sudden high force contractions of the biceps brachii muscle are a common cause of SLAP lesions. This injury often occurs with a sudden eccentric load on the biceps, such as catching something heavy that is falling or sudden deceleration of the throwing arm. When the muscles have to suddenly contract (to stop motion) it puts a high force load on them. This is often what causes rotator cuff injury. Because the biceps brachii also has to decelerate the forceful elbow extension when you throw, it must contract suddenly to stop that motion. The sudden pulling on the biceps is transmitted to the superior margin of the labrum. This injury is common in athletes like baseball players, whose sports require a lot of throwing.

The SLAP lesion is very difficult to identify with physical examination and is even challenging with certain high-tech diagnostic studies because of the soft tissue involvement. However, there are certain indications that one can look for that are likely indicators of a labral injury. There are certain clinical signs such as popping or clicking of the shoulder during motion that is accompanied by pain deep in the shoulder. In the history, there would be trauma that involved sudden forces to the shoulder.

If you are suspicious of a labral injury, the best protocol is to refer the client to an orthopedic physician, one specializing in shoulder injuries, so that the injury may be diagnosed and possible treatment initiated (this condition can require surgery).

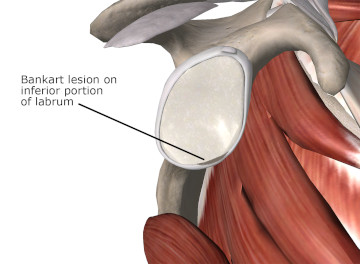

The second common type of labral injury is called a Bankart lesion or Bankart tear. It is a tear to the anterior and inferior portion of the labrum near where it blends in with inferior glenohumeral ligament (Figure 4). This portion of the joint capsule and labral complex can also be stressed in repetitive overhead motions, such as throwing or serving a tennis ball. The Bankart lesion is also relatively common when the shoulder is dislocated as the humeral head pulls on the anterior inferior portion of the capsule as it moves out of the joint.

Figure 4

Inside view of the glenohumeral joint showing a Bankart lesion along the inferior labrum

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 5 application

Sudden forceful trauma to the joint, such as falling on an outstretched arm, is another cause of labral tears. The labral tear may occur from excessive tensile loads from the joint capsule or from the humeral head being thrust against the back side of the labrum. In some more traumatic cases of the Bankart tear, a chunk of bone gets pulled away when the inferior glenohumeral ligament and labrum pull away from the glenoid fossa. This is called a Bankart fracture and requires an arthroscopic surgical procedure to repair.

Complications from Labral Injury

There are a number of complications that may develop as a result of labral tears. First, because of the poor innervation and circulation to this tissue, the tear may often be significantly advanced before it causes enough pain to be recognized by the client.

Because the labrum is designed to hold the humeral head in position, a tear or disruption in the labral complex can lead to shoulder instability. Increased instability in the shoulder may then predispose the person to dislocations, or other shoulder pathologies such as impingement or rotator cuff pathology.

Another complication that may develop are paralabral cysts. As a result of the labral tear, there is increased fluid in the area that leaks out of the capsule. Once that fluid escapes the capsule, it is still contained within a small cyst. These paralabral cysts usually occur from SLAP lesions and are often found around the suprascapular notch. They have been known to cause entrapment of the suprascapular nerve.2 Because the suprascapular nerve innervates the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, this cyst could cause rotator cuff dysfunction due to impaired muscular innervation.

To Massage or Not?

The first question to answer when determining if massage is appropriate is whether or not it is likely to cause an adverse or detrimental effect. There is no indication that massage or any gentle range-of-motion activities performed within normal limits would likely cause any adverse effect on labral tears.

Once it is determined that massage is not likely to cause any adverse event, the next question is could it be beneficial in treating the injury. In this case, labral tears are too deep in the shoulder joint and the labrum is a non-contractile tissue that won’t be accessible to or benefitted by palpation. Therefore massage will not have any direct effect on resolving labral tears. However, as in many situations that does not mean that massage is not of any benefit.

Injuries such as Justin’s labral tear are frequently accompanied by resulting dysfunctional mechanics at the joint. Myofascial trigger points may develop around this region, or other biomechanical imbalances may occur as the shoulder attempts to compensate for pain, instability, or loss of function associated with the injury. Massage can certainly be used to help restore biomechanical balance in the shoulder in these situations.

The key take away lesson here is that details from the client history are very important along with the physical examination. In Justin’s case, information provided in the history along with symptoms of deep pain and clicking sounds with movement of the shoulder were strong indications of labral injury. Massage treatment can easily be employed in a situation like this concurrent with other treatments to address the labral tear.

We are sometimes faced with conditions that need to be treated first by another healthcare professional. It is very important and helpful for the massage therapist to have an understanding of these pathologies and be able to ascertain when they might be occurring, and make an appropriate referral.

It is also imperative for us to understand the limitations of what we do so we don’t give a client false hopes about what massage can accomplish. Once a condition like this is diagnosed, massage is an excellent adjunct treatment that can prevent further issues.

Resources:

- Khan A, Chew F. Glenoid Labrum Injury MRI. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/401990-overview. Accessed February 7, 2015.

- Pillai G, Baynes JR, Gladstone J, Flatow EL. Greater strength increase with cyst decompression and SLAP repair than SLAP repair alone. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1056-1060.