Understanding Shoulder Separation

- Whitney Lowe

Understand shoulder separation and the misconceptions surrounding it, as well as how to accurately identify and treat the condition.

Introduction

There are numerous orthopedic disorders that develop a common name by which they are more frequently known. Examples include runner’s knee or tennis elbow. A shoulder separation is another condition that has come to be known by its common name, although sometimes that is misleading.

The term shoulder separation is often misconstrued as a dislocation of the humeral head from the glenoid fossa, but that is inaccurate. The glenohumeral joint is the primary joint of the shoulder, but there are three other significant articulations—the scapulo-thoracic articulation, the sternoclavicular joint, and the acromioclavicular joint. A shoulder separation is a sprain to the ligaments of the acromioclavicular complex.

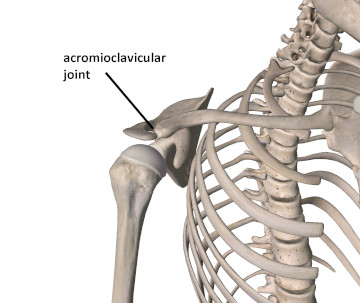

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is the junction between the distal end of the clavicle and the acromion process of the scapula (Figure 1). The AC joint is a standard diarthrodial joint (one with a cavity), but it may sometimes contain a fibrocartilaginous disc. At this joint the clavicle joins the acromion and acts as a strut to improve stability in the shoulder complex. Therefore there is very little motion at the AC joint.

Figure 1

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 3 application

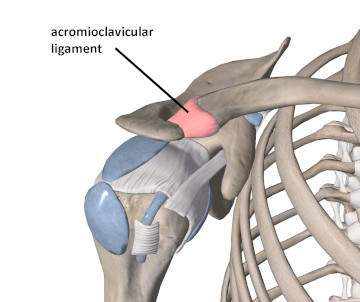

Stability in the AC joint is maintained through several important ligament structures. The primary stabilizing support at this joint is the acromioclavicular ligament (Figure 2). The acromioclavicular ligament provides stability against horizontal shear forces at the AC joint, and consequently provides the primary horizontal stability.

Figure 2

The acromioclavicular ligament

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 3 application

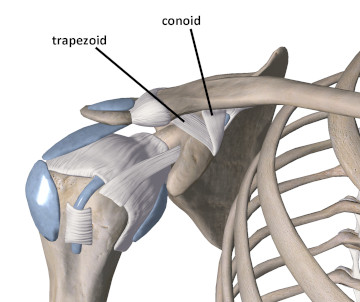

Additional stability at the joint is created by two other ligament structures that together are referred to as the coracoclavicular ligaments. They span between the coracoid process and the clavicle. Both of these ligaments, the trapezoid and the conoid, are named for their shape (Figure 3). The primary function of the coracoclavicular ligaments is to produce vertical stability.

Figure 3

The coracoclavicular ligaments

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 3 application

Description of Pathology

A shoulder separation is defined as a sprain to the ligaments supporting the AC joint. Most injuries occur from falling directly on the shoulder or being hit with something heavy. If the injury occurs from falling and hitting the ground, the sprain may be more likely if the glenohumeral joint is in an adducted position (arm at the side). When the arm is adducted, the lateral shoulder region is the first contact point when the shoulder hits the ground. This mechanism of injury happens often in collision sports, and because more men than women are involved in these types of activities, shoulder separations are much more likely to occur in men than women.

A sprain to the AC joint complex may occur in a number of different ways. A classification proposed for AC sprains in 1984 by Rockwood has since been adopted and widely used to describe the severity of the problem.1

Type I: Local tenderness is present, but there is no anatomical deformity, and no complete tear of either ligament.

Type II: Local tenderness, and there is some recognizable anatomical deformity (often the “raised” clavicle). There is a tear of AC ligament, but the coracoclavicular ligaments are intact. There is no marked elevation of lateral end of clavicle.

Type III: There is a great deal of tenderness and significant anatomical deformity associated with damage to the AC ligament. There is damage to the coracoclavicular ligaments as well. In some instances there may be clavicular fracture associated with Type III – VI. There is usually between 25% – 100% superior translation of distal clavicle.

Types IV – VI involve complete rupture of the associated ligaments of the AC joint.

Type IV: Complete rupture of ligaments that are supporting the AC joint. The distal clavicle is impaled posteriorly into trapezial fascia. Usually a posteriorly directed force to the distal end of the clavicle will be responsible for an injury of this type.

Type V: Ligament rupture with superior translation of the distal clavicle that may be between one and three times the clavicle’s diameter in displacement.

Type VI: Ligament rupture with inferior translation of distal clavicle below the coracoid or acromion processes.

Type I and II are the most common and will occur much more often than the more severe dislocations described in Types III – VI.

How to Identify the Separation

Most often there is a history of traumatic force to the anterior/lateral shoulder region. Sometimes the condition may result from chronic overuse. Yet, repetitive overhead motions like throwing activities may cause progressive weakness in the joints and make them susceptible to sprain.

Because the AC joint is so superficial, it is easy to palpate the region for tenderness, which is a likely factor in all six types of shoulder separation. In a more severe sprain, a visible anatomical deformity, such as the distal clavicle protruding from the edge of the acromion, may be visible.

The individual is also likely to have pain with a variety of motions of the shoulder that stress the damaged ligaments of the AC complex. In particular, movements involving horizontal adduction of the arm, both active and passive, are likely to reproduce the client’s complaint.

Fractures may accompany severe shoulder separations, so the client should seek proper evaluation from a physician if there are indications of severe acromioclavicular injury that may indicate fracture possibilities (characteristics of Type III – VI sprains).

Treatment Strategies

Treatment methods for shoulder separations will depend on the severity of the injury. Type I sprains are usually treated with ice applications to reduce initial swelling, and rest from any offending activities. Type II conditions will be treated in the same manner as type I, with the addition of a sling or harness to give the region a period of immobilization to promote proper ligament healing. Type III injuries may be treated with surgery, but they are increasingly treated in the same manner as above, except for a longer period for usage of the sling (usually about 2-4 weeks). Gentle mobilization and strengthening will follow removal of the sling. Shoulder separations that fall into type IV – VI usually require surgical intervention.

The onset of muscle spasm and guarding following immobilization is a prominent indication for the use of massage in the rehabilitation process. Few methods are as effective as massage in reducing the overall hypertonicity in surrounding shoulder girdle muscles. Deep longitudinal stripping techniques and static compression methods are used to treat myofascial trigger points and muscle tightness associated with the sprain.

Deep friction massage applied directly to the acromioclavicular ligament is beneficial for stimulating collagen production in the damaged tissue and reducing excess fibrosis during the healing process. The practitioner should wait until after the initial inflammatory stage (usually the first 72 hours) before administering friction treatment directly to the damaged ligaments. Injuries that are type III and higher require a longer period prior to applying friction treatments to make sure that further ligament damage doesn’t result. It is very helpful to consult with the client’s other health care professionals about when massage would be appropriate depending on the severity of the injury

While shoulder separations are not necessarily frequent, they are not uncommon either. Massage should not be the sole treatment for a shoulder separation, but it can play a very important role in addressing the recovery from this injury. Even in the more severe sprains, massage can be an important part of the rehabilitation process in order to regain proper function in the shoulder girdle.

References

- Rockwood C. Injuries to the Acromioclavicular Joint. In: Rockwood C, Green D, eds. Fractures in Adults. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1984:860–910.