An Inside Look at Bicipital Tendinopathy

- Whitney Lowe

Introduction

Bicipital tendinopathy is a frequent source of anterior shoulder pain. The condition usually arises from overuse or adverse forces affecting the tendon. It is common with overhead shoulder movements like swimming, tennis, or throwing. It can also stem from work-related motions. Distinguishing its pain from similar shoulder issues requires thorough assessment for accurate recognition.

Anatomical Overview

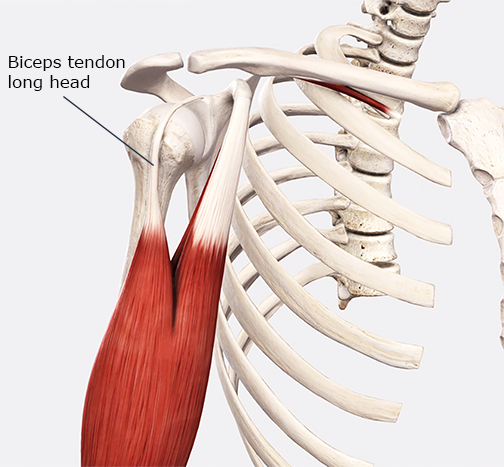

The biceps muscle has two tendons of origin. The short head originates from the coracoid process. The long head originates from the supraglenoid tubercle above the glenoid fossa. The two heads converge and culminate in a shared attachment at the tuberosity of the radius. Bicipital tendinosis rarely affects the short head. The long head’s anatomical path causes it to be susceptible to this condition. The long head’s tendon begins at the supraglenoid tubercle. It then courses under the acromion process before exiting the glenohumeral joint capsule. Then it takes a right-angle turn and courses inferiorly in the bicipital groove (Image 1). The bicipital groove is the space between the greater and lesser tubercles.

The long head of the biceps brachii.

Image courtesy of Complete Anatomy

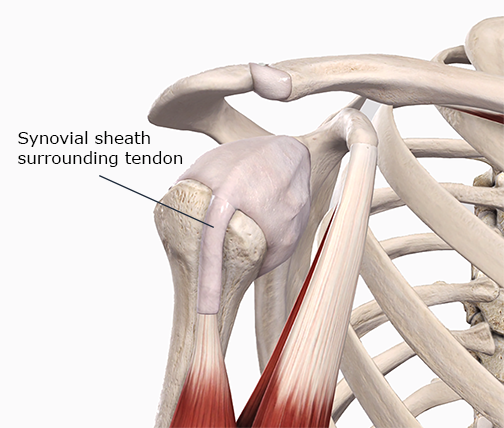

This path subjects the tendon to significant friction, especially during common shoulder motions. To mitigate this friction, a synovial sheath encases the tendon. The synovial sheath helps reduce friction between the tendon and bone (Image 2). Sheathed tendons are most common in the distal extremities. The long head of the biceps stands out as a sheathed tendon not in a distal extremity.

The synovial sheath surrounding the biceps tendon long head.

Image courtesy of Complete Anatomy

Pathology Overview

Bicipital tendinopathy encompasses two primary conditions: tendinosis and tenosynovitis. Tendinosis involves the degradation of the tendon’s collagen matrix. The term “tendinosis” is now preferred over “tendinitis.” This is because most of the collagen degeneration disorders have minimal inflammatory activity. Tenosynovitis is an inflammatory condition of the synovial sheath. Besides inflammation, there may also be adhesion between the tendon and its sheath.

The biceps tendon must be mobile within its synovial sheath. There must also be minimal friction between the tendon and the bone of the bicipital groove. Excess friction or pressure can lead to tendinosis or tenosynovitis. These conditions may also coexist. It may not be easy to distinguish between them, but the treatments for each are similar.

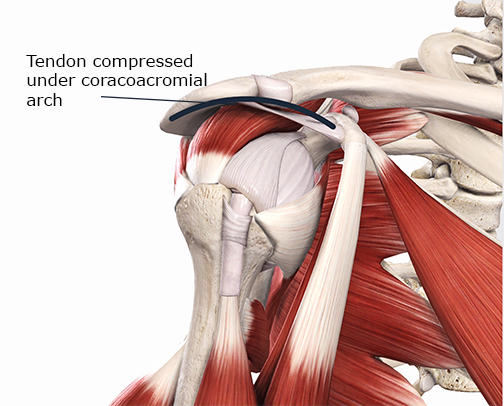

Subacromial impingement can also contribute to bicipital tendon pathology. In subacromial impingement, the tendon is pinched against the acromion process. It may also press against the coracoacromial ligament, causing damage (Image 3). Subacromial compression happens most often during shoulder flexion or abduction. Thus, bicipital tendinosis can be secondary to other regional biomechanical or anatomical challenges. Check out our YouTube video if you’d like a better visual understanding of the condition.

Compression of the biceps tendon under the coracoacromial arch.

Image Courtesy of Complete Anatomy

Bicipital tendon pathology may also result from excessive forearm supination or elbow flexion. These forearm and elbow movements are common in many repetitive motion occupations.

The transverse humeral ligament also influences the tendon’s movement within the bicipital groove. Laxity in this ligament can lead to tendon displacement out of the groove. Repetitive tendon displacement can cause tendinosis or tenosynovitis.

Assessment Strategies

Recognizing biceps tendon pathology begins with a thorough history. Ask about any repetitive shoulder motions or overhead upper extremity motions. Also, inquire about any motions that use strong biceps actions. That would include shoulder flexion, elbow flexion, and forearm supination.

Also, note that tendinopathy may occur without some of these biomechanical factors. Tendon pathology can result from certain medications, such as fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Note that the antibiotics are usually unrelated to any musculoskeletal complaint. As a result, clinicians may miss the connection between antibiotics and tendon disorders.

Pain is most common on the front of the shoulder and may extend down the arm. Pain is often aggravated at night due to shoulder compression from side sleeping. Night pain is also common with rotator cuff disorders. It is common for rotator cuff pathology to exist alongside bicipital tendinopathy.

Palpation is crucial in recognizing bicipital tendinopathy. The tendon feels like a pencil-like structure on the anterior shoulder. You are pressing through the deltoid to reach the bicipital tendon, so it may be challenging to identify. Gently rotating the shoulder in medial and lateral rotation can help identify the tendon. Tenderness and pain in the tendon with palpation are common in tendinopathy.

Pain is often reproduced with movements that strongly load the biceps muscle. Flexion (of the shoulder or elbow) and forearm supination are common painful actions. Passive movements that shorten the muscle-tendon unit are generally painless. Yet, pain may occur during passive shoulder flexion or abduction with tendon impingement.

Performing simultaneous shoulder and elbow extension (actively or passively) may also reproduce pain. In this motion, you are stretching the muscle-tendon unit, which can be painful. There may also be pain in any isometric action of the biceps.

Speed’s test is a standard special orthopedic test to recognize bicipital tendinopathy. Check out the video link to see the performance of this test. Also, consider the possibility of other conditions with similar symptoms. These include rotator cuff pathology, degenerative arthritis, acromioclavicular joint sprains, and calcific tendinitis. Pain locations may be similar. Yet other factors in history and examination can help discriminate between them.

Orthopedic Medical Massage Treatment

Initiating treatment for tendinopathy involves reducing or modifying activities that exacerbate the condition. A critical factor in any treatment is rest from offending activity. That doesn’t mean complete rest and inactivity. It means to reduce the activity overload to a manageable level. Applying a controlled load on the tendon can stimulate healing processes. So exercise and movement can be a crucial part of effective treatment.

One of the more common methods of soft-tissue treatment is deep transverse friction. Former descriptions of friction treatment focused on breaking up scar tissue. There was a belief that this helped realign torn tendon fibers. Now, we know that torn fibers are not the primary cause of tendon pathology. Current narratives focus on a different mechanism for the effectiveness of friction. Evidence suggests that pressure and movement applied to the tendon stimulate fibroblast proliferation. This process is integral to the tendon repair.

Use caution when applying deep friction to the bicipital tendon in a transverse direction. If the bicipital groove is shallow, you could force the tendon out of the groove. This could also happen if there is laxity in the transverse humeral ligament. A safer alternative is longitudinal friction applied along the direction of the tendon.

Addressing muscle tightness is a crucial part of tendinopathy treatment. Various techniques can be effective for this treatment. One of the most beneficial methods involves active engagement techniques. These techniques involve active muscle contraction along with soft-tissue manipulation. The active muscle contraction provides a beneficial load on the tendon. That low-level load can be helpful in the healing process. You can explore this approach and other helpful approaches inside our shoulder course.

Understanding bicipital tendinopathy is a critical factor for treating shoulder pain. This improved understanding will significantly enhance your treatment success. Besides treatment, your role includes educating clients on health maintenance and injury prevention. The better you understand various conditonfs, the better you can help them.

Want more help in recognizing soft-tissue pathologies? Grab a copy of our assessment cheat sheet! It will help you better recognize soft-tissue pathologies. Your clients will love you for it!