Rolling With It: Overpronation’s Influences Explored

- Whitney Lowe

Introduction

If you work with competitive runners or clients who are constantly on the move, chances are you’ve come across overpronation—sometimes called hyperpronation—more than a few times. This common gait pattern shows up frequently in active individuals and can play a role in a wide range of lower extremity issues, from nagging foot pain to chronic knee problems. But here’s the twist: overpronation isn’t always the villain. In some cases, it’s just an incidental finding with no connection to the client’s current complaint. That’s why it’s essential for clinicians to develop a sharp eye for when overpronation matters—and when it doesn’t. So, before we dive into treatment strategies, let’s start by defining exactly what overpronation is.

Defining Pronation and Overpronation

Pronation and supination are anatomical terms often associated with forearm and wrist movements. In the context of the foot and ankle, these terms apply differently. Pronation of the foot and ankle complex occurs naturally during walking or running gait cycles. Therefore, stating that a person has issues simply because they pronate their foot is inaccurate, as pronation is a normal aspect of walking. The problem arises with excessive pronation. Overpronation indicates pronation movement that is excessive or occurs too rapidly during the gait cycle. However, there isn’t consensus in the scientific literature about what constitutes excessive movement and how to define it, making accurate descriptions of overpronation challenging.

In the forearm, pronation is a single-plane movement involving the turning over of the wrist and hand. In contrast, foot and ankle pronation is more complex. Pronation in the foot doesn’t occur solely in one of the three cardinal planes: sagittal, frontal, or transverse. It is a diagonal movement encompassing all three planes. Consequently, it is defined as a combination of dorsiflexion (in the sagittal plane), eversion (in the frontal plane), and abduction—more commonly referred to as turnout of the foot (in the transverse plane). Thus, pronation is a multi-planar movement that occurs during normal gait.

Figure 1

Three movements of pronation: dorsiflexion, eversion, and abduction

The diagonal movement of pronation is more easily visualized during a non-weight-bearing position (Figure 2). It is a little more challenging to visualize pronation when the foot is in a weight-bearing position because the foot can’t move freely through space. Pronation occurs during the mid-stance (weight-bearing) portion of the gait cycle. In a weight-bearing position instead of the foot moving in relation to the leg, the foot is stationary on the ground and the leg moves in relation to the foot in the same diagonal plane across the foot.

Figure 2

Pronation in a non-weight bearing position

Primary Causes

Overpronation, characterized by excessive or rapid pronation during gait, can lead to dysfunctional biomechanics and various pain complaints. Several key factors may increase the risk of overpronation.

Tibialis Posterior Muscle Dysfunction

Functional weakness of the tibialis posterior muscle is a common cause of overpronation. Located in the posterior compartment of the leg, deep to the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, the tibialis posterior plays a critical role in foot mechanics. While its primary actions include plantar flexion and inversion of the foot, it also controls the amount of foot pronation during gait by acting eccentrically to decelerate pronation. When the tibialis posterior fails to adequately resist pronation, overpronation can occur, leading to conditions such as posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD). PTTD is characterized by pain and swelling along the tendon and can progress to adult-acquired flatfoot deformity if left untreated.

Deltoid Ligament Laxity

The deltoid ligament complex on the medial side of the ankle also plays a crucial role in preventing overpronation. This triangular-shaped ligament resists excessive calcaneal eversion, a significant component of overpronation. Injuries or genetic factors leading to ligamentous laxity can loosen the deltoid ligament, resulting in hypermobility of the foot and ankle complex. This hypermobility contributes to overpronation and may lead to chronic medial ankle instability if not properly addressed.

Excessive Body Weight

Excessive body weight can contribute to overpronation by placing additional stress on the foot’s arch-supporting structures. This increased load can lead to arch collapse, causing the foot to roll toward the medial side. The loss of an adequate arch, observable in a static standing posture as pes planus (flatfoot), becomes more pronounced during the gait cycle, resulting in overpronation. It’s important to note that pes planus can also occur due to genetic factors, not solely from being overweight.

Knee Alignment Abnormalities

Faulty knee alignment, such as genu valgum (knock-knees), can also lead to overpronation. Genu valgum causes the knees to bend inward, altering weight distribution through the lower extremity. This inward knee positioning directs more weight toward the medial side of the foot during gait, increasing the likelihood of overpronation.

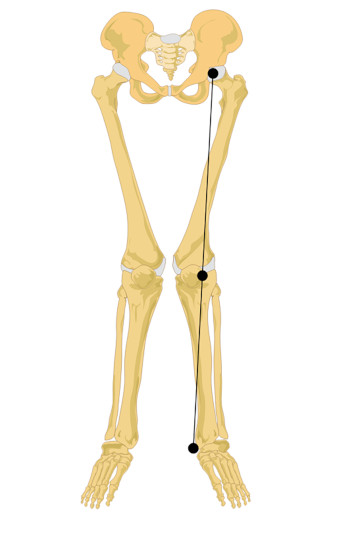

Figure 3

Genu valgum (knock knees)

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

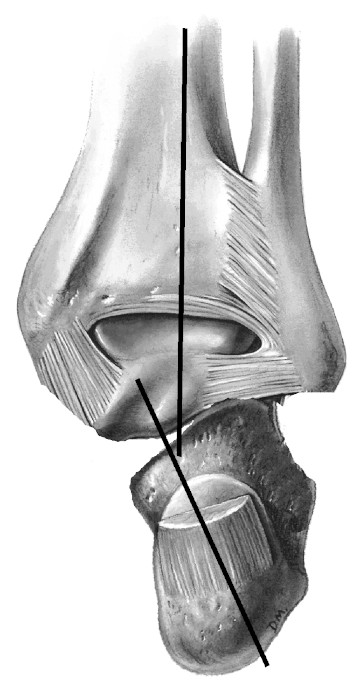

A valgus angulation is one in which the distal end of a bony segment deviates in a lateral direction. At the knee, the valgus angulation is named for the lateral deviation of the distal tibia. There can also be a valgus angulation to the calcaneus where the distal end of the calcaneus deviates in a lateral direction (Figure 4). Calcaneal valgus is also called subtalar eversion. Calcaneal valgus is generally visible in a standing position and is best viewed from the back side of the heel. The will heel appear to be angling in a lateral direction. This postural deviation can also be viewed from the front side of foot and causes a small section of the heel to stick out toward the lateral side of foot and since only a small portion of it is visible sticking out to that side it is sometimes called a peekaboo heel.

Figure 4

Posterior view of the right foot showing lateral deviation of the distal calcaneus in calcaneal valgus

Mediclip image copyright (1998) Williams & Wilkins. All Rights Reserved.

Overpronation can also be a cause of other lower extremity disorders. Plantar fasciitis, tarsal tunnel syndrome, Baxter’s neuropathy, and posterior shin splints may all be aggravated from overpronation, especially in runners. There is also a strong likelihood that overpronation plays a major role in a condition called hallux valgus, which eventually leads to the formation of bunions on the medial side of the foot at the metatarsophalangeal joint.

As noted above, there are structural challenges that may point to the possibility of overpronation. However, because pronation is really a dynamic movement and not just a static position, it is best evaluated during the gait cycle, such as watching a person’s foot strike and gait pattern on a treadmill. However, that is generally not practical for most massage therapists. Another factor that can be helpful in recognizing overpronation is examining the wear pattern on the bottom side of the client’s shoe. This will only work if the shoes have been worn a significant amount so that some wear pattern is evident. A person who overpronates will tend to have a greater degree of wear on the medial side of the shoe.

Treatment Considerations

In traditional orthopedic approaches, overpronation is generally addressed with orthotics to help change the biomechanical pattern of the foot and ankle complex. The goal is to re-stack the foot and ankle complex in a more vertical position and prevent it collapsing towards the medial side and overpronating during weight bearing.

Another common treatment strategy is to encourage strengthening of the tibialis posterior and other associated muscles that resist overpronation. It is challenging to target this specific group of muscles, but various foot and ankle movements can be done with varying levels resistance to help develop greater strength in these muscle groups. There can be a fundamental error with this approach, however. You can develop greater strength in a muscle group, but if the motor pattern ingrained in the nervous system still allows for dysfunctional mechanics and perceives this as normal, increasing strength in those muscles is not necessarily going to change the dysfunctional mechanics. As a result, the person is still likely to continue overpronating. If the strengthening is done in conjunction with orthotics or other interventions that alter motor recruitment patterns, there is a greater likelihood that they will have lasting results.

So what role does massage or soft-tissue treatment play in addressing overpronation? While there are no research-based treatment protocols, there are a number of common suggestions for helping overpronation with massage. Suggestions include moderately deep and tissue-specific compression and stripping techniques along the plantar surface of the foot and along the tibial border to access the deep posterior compartment (Figure 5). The described intention of these approaches is to increase extensibility of the tissue and make it free to move and reduce overuse trauma. However, a primary issue in overpronation is that the tibialis posterior is not functioning adequately to resist overpronation, so the problem is not that the muscle is too short or contracted. Therefore, the goal may be to reduce hypertonicity, but generally should not be to increase too much extensibility in that tissue.

Figure 5

Deep longitudinal stripping along the tibial border to best access tibialis posterior

There are some massage technique descriptions which advocate stimulating the muscle and encouraging it to ‘turn on’ or increase motor activity and gain strength. However, there is no significant research to support the idea that any massage technique can strengthen a muscle. That doesn’t mean that massage is not beneficial in addressing overpronation, but the way in which we use it for this purpose may be different than what we generally think of.

Our understanding of the primary effects of massage has changed in recent years. Some of the most profound effects seem to be mostly associated with changes in the nervous system. Consequently, these approaches are helpful to improve proprioceptive responses from the foot and ankle complex to adjust faulty biomechanical patterns. Yet, remember that just because a person is overpronating does not mean there is a pathological issue that has to be fixed. Many people can function just fine with less than ideal biomechanical patterns. The key challenge for us is to determine if it is a mechanical pattern that is leading to other soft-tissue pain and injury problems or if it is an incidental finding that may not necessarily be a root cause of the client’s current complaint.

Changing the neurological and motor control associated with a particular biomechanical pattern is a complex process. We now recognize that many soft-tissue interventions aren’t mechanically changing tissue as much as they are helping make new connections in the brain and nervous system with how the tissues feel and function. Massage therapy remains one of the most powerful and effective strategies for soft-tissue intervention, so despite the fact that we may not be changing structure within the body significantly, what we’re doing in treating conditions like overpronation is still incredibly valuable.