Pectoralis Minor Syndrome

- Whitney Lowe

A look at neurovascular compression by the pectoralis minor muscle (pectoralis minor syndrome), a common variation of thoracic outlet syndrome.

Nerve entrapment can occur in a number of locations in the upper extremity. Nerve compression symptoms can be similar from these various sites, which is why identifying the specific location of the entrapment is challenging. One of the most common upper extremity nerve entrapment problems is thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS). However, there are multiple variations of thoracic outlet syndrome, so even that term is not an accurate depiction of what may be occurring for the client.

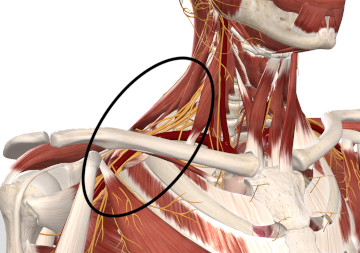

True neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is an impingement of the neurovascular structures in the thoracic outlet region (Figure 1). The impingement is most often caused by a structure called a cervical rib. The cervical rib is a bony extension of the transverse process of the 7th cervical vertebra that loops around in an anterior direction toward the sternum just like a rib attachment.

Figure 1

The thoracic outlet region

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Complete Anatomy application

However, there are four variations of TOS and the cervical rib variation is the least common of the four. The other three variations are anterior scalene syndrome, costoclavicular syndrome, and pectoralis minor syndrome. In this issue we explore neurovascular compression by the pectoralis minor muscle (pectoralis minor syndrome), which is a much more common variation of thoracic outlet syndrome and something massage therapists are likely to encounter.

ANATOMICAL BACKGROUND

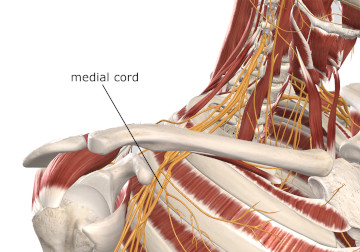

The pectoralis minor muscle attaches superiorly to the coracoid process of the scapula, and inferiorly to the anterior surface of ribs 3, 4, & 5. Three separate cords of the brachial plexus as well as the axillary artery and vein pass between the pectoralis minor muscle and the upper rib cage. The three cords of the brachial plexus are the lateral, posterior, and medial cords. The medial cord of the brachial plexus is the branch most involved in pectoralis minor syndrome (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Medial cord of the brachial plexus

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Complete Anatomy application

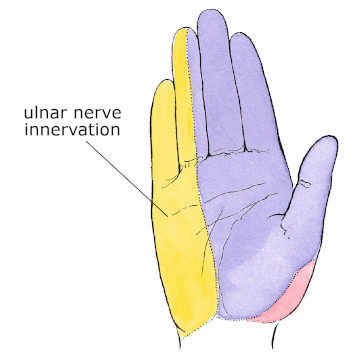

The medial cord of the brachial plexus primarily contributes to the ulnar nerve in the upper extremity. Therefore, most nerve compression symptoms from pectoralis minor syndrome appear in ulnar nerve region of cutaneous innervation in the hand (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Ulnar nerve innervation in the hand

Mediclip image copyright (1998) Williams & Wilkins. All Rights Reserved.

DESCRIPTION OF PATHOLOGY

Muscular tightness and postural challenge appear to be the most common causes of nerve compression by the pectoralis minor. There are three muscles that attach to the coracoid process: pectoralis minor, coracobrachialis, and the short head of the biceps brachii muscle. If any or all these muscles are tight, they may pull the scapula and coracoid process in an inferior direction. Forward depression of the coracoid process narrows the space between the pectoralis minor and the upper rib cage and may pin the neurovascular structures against the rib cage.

In addition to muscle tightness, this condition may occur from postural distortions such as upper thoracic kyphosis (forward head posture) and the frequently accompanying internally rotated shoulders. Activities like using the arm overhead a great deal or carrying heavy loads on the affected side may also aggravate the condition. With the arm overhead, the brachial plexus gets bowstrung under the pectoralis minor muscle and is more susceptible to compression pathology. Heavy loads carried in the upper extremity can depress the scapula by pulling the whole shoulder girdle in an inferior direction. The resulting postural challenge may increase the potential for brachial plexus compression by the pectoralis minor muscle.

ASSESSMENT

The most common symptoms to be felt from pectoralis minor syndrome are pain or paresthesia sensations in the ulnar distribution of the hand (Figure 3). The client may also experience intermittent aching along the medial aspect of the forearm and hand. Motor function of the muscles supplied by the ulnar nerve may also be impaired. This will be most evident by a wasting or atrophy of the thenar muscles of the palm (muscles of the palm near the thumb).

Arterial flow can also be compromised in pectoralis minor syndrome. Symptoms of arterial compression include coolness, fatigue, edema, heaviness, or cyanosis (darkening) of the skin in the affected upper extremity. Any of the neurovascular symptoms may be irritated by carrying heavy objects in the affected arm or by wearing a heavy backpack or handbag, which further compresses the vascular structures. Clients may also report symptoms being aggravated at night by sleeping on their side or sleeping with their hand up over their head.

Certain positions may also aggravate symptoms during physical examination. Movements of shoulder flexion or full abduction (either passively or actively) may reproduce symptoms if the ending position of full flexion or abduction is held for a few moments. Holding the arm in full abduction is a common special orthopedic test, called the Wright’s abduction test.

In this procedure the client brings their arm overhead to a fully abducted position and holds it. If the symptoms are reproduced within about 30 seconds, this is considered a positive test for neural impingement under the pectoralis minor muscle. It doesn’t matter whether this movement is performed actively or passively. The resulting compression should be the same in either situation.

In addition to the other variations of thoracic outlet syndrome mentioned earlier, several other conditions may have symptoms similar to pectoralis minor syndrome. Ulnar neuropathy in the wrist (Guyon’s canal syndrome) as well as cubital tunnel syndrome in the elbow may both have similar symptoms, as they both involve ulnar nerve compression as well.

While ulnar nerve compression by the pectoralis minor is the most common, the pectoralis minor could also compress the median or radial nerves. If the median nerve is compressed by the pectoralis minor, this condition could be easily mistaken for carpal tunnel syndrome, which is the most frequently occurring upper extremity nerve pathology. Myofascial trigger points may refer pain or other neurological sensations down the upper extremity and can often be mistaken for nerve compression as well. The trigger point referrals can usually be reproduced with pressure on the affected muscles, and that is one helpful way to distinguish trigger point involvement from brachial plexus compression by the pectoralis minor.

TREATMENT

Conservative treatment is the most appropriate way to address this problem as surgical approaches generally have a low success rate. The most effective treatments include postural awareness and retraining along with soft tissue manipulation aimed at the entire shoulder girdle muscles. Massage treatments to the entire shoulder girdle can help restore ideal biomechanical balance in this region and increase proprioceptive awareness that can help enhance postural retraining. Treatment and stretching techniques are often aimed at encouraging relaxation in the pectoralis minor muscle. This muscle is hard to stretch because it is difficult to pull the coracoid process very far in a superior direction away from the upper rib cage, which is required to fully stretch the muscle.

Techniques that do not further compress the brachial plexus lying right under the muscle are best. Instruct the client to let you know if they experience any neurological sensations going down the upper extremity while you work in this region. Don’t continue pressure on any region that aggravates the existing neurological symptoms.

It is common for clients presenting with neurological symptoms in the upper extremity to be quickly diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome, because it is so common. However, other conditions like pectoralis minor syndrome may often be the real culprit. Because the main problem in pectoralis minor syndrome revolves around muscle tightness, this is a condition that can respond very well to appropriate massage interventions.