Radial Tunnel Syndrome – Maybe That’s Not Tennis Elbow…

- Whitney Lowe

A look at Radial Tunnel Syndrome, a condition often mistaken for lateral epicondylitis, its pathology and how to effectively assess and treat it.

Introduction

Lateral epicondylitis, commonly referred to as tennis elbow, is one of the most prevalent upper extremity overuse conditions. Originally perceived as an inflammatory condition of tendon fiber tearing, it is now recognized to result from non-inflammatory collagen degeneration within the tendon as a result of overuse. Massage can be very effective for addressing this problem because pressure and movement applied to the tendon is one of the most effective methods of encouraging fibroblast proliferation in helping to rebuild the damaged collagen.

However, lateral elbow and forearm pain may come from other causes and can easily be mistaken for lateral epicondylitis. In such a case, the standard treatment protocol for epicondylitis of deep friction massage applied to the lateral elbow region could aggravate the condition and make it worse. If the standard protocol for addressing lateral epicondylitis is ineffective, it could be because the primary dysfunction is something different.

Radial tunnel syndrome (RTS) is commonly mistaken for lateral epicondylitis. It is a nerve compression pathology affecting the radial nerve. RTS is also frequently referred to as ‘resistant tennis elbow’ because the symptoms can be so similar to tennis elbow but resistant to the standard treatments.

ANATOMICAL BACKGROUND

The radial nerve courses around the posterior aspect of the upper arm along the spiral groove of the humerus. It then crosses the anterior aspect of the elbow, before continuing down the forearm. Just distal to the elbow the radial nerve divides into its two terminal branches, superficial and deep. The superficial radial nerve is sensory, while the deep branch, which comprises the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN), carries mostly motor fibers. It is the PIN that is involved in RTS.

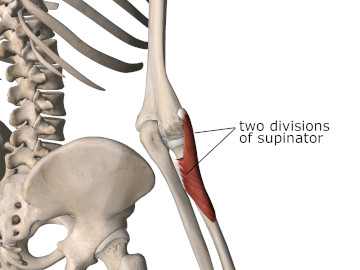

The supinator muscle has two separate divisions. One comes off the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, and has fibers that also originate from the radial collateral and annular ligaments. The other supinator division originates on the supinator crest and the fossa of the ulna (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Posterior view of the elbow showing two divisions of the supinator muscle

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 5 application

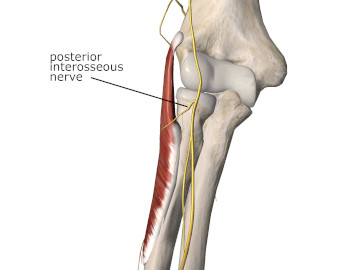

The posterior interosseous nerve passes between the two divisions of the supinator muscle as it enters the radial tunnel (Figure 2). The radial tunnel is bordered on one side by the tendons of the extensor carpi radialis brevis, the extensor carpi radialis longus, and brachioradialis. The tendons of the biceps brachii and brachialis make up the opposite wall of the tunnel. The capsule of the radiocapitular (radius and capitulum of humerus) joint makes up the floor of the tunnel.1

Figure 2

Anterior view of the elbow showing the PIN as it enters the radial tunnel

Image is from 3D4Medical’s Essential Anatomy 5 application

PATHOLOGY

Compression of the posterior interosseous nerve in the radial tunnel is known as radial tunnel syndrome. There are several different factors that may cause radial nerve compression in this region. Trauma to the elbow causing displacement of bones in the elbow joint is a common cause. Small cysts or tumors can also compress the nerve in the tunnel. The most common cause of PIN entrapment in the radial tunnel is tendinous bands at the edge of the tunnel that press on the nerve.

The symptoms of other common upper extremity nerve compression pathologies such as carpal tunnel syndrome or cubital tunnel syndrome are dominated by sensory aberrations such as pins and needles, electrical sensations, or sharp stabbing pain. These strong sensory symptoms are predominantly the result of cutaneous sensory fibers within the nerve being aggravated.

Nerve compression in radial tunnel syndrome is a bit different because the posterior interosseous nerve is predominantly a motor nerve and carries very few sensory fibers. However, it does carry sensory fibers from the muscles it innervates and related joint areas so it is not completely devoid of sensory fibers. The pain felt from radial nerve compression is more likely to be perceived in the muscle belly as that is where the sensory fibers are coming from. This pain pattern in RTS is in contrast to that of epicondylitis where the primary tenderness is in the tendon fibers very close to the tendon attachments at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus.

Because the PIN is predominantly a motor nerve, muscle weakness or difficulties with upper extremity dexterity are common. The primary muscles affected are the extensors of the wrist and fingers. Forearm pain may accompany weakness when the extensor muscles are contracted significantly because the sensory fibers in the affected muscles are being stimulated. Keep in mind that motor or sensory symptoms may exist together or without the presence of the other.

The symptoms of RTS may develop suddenly or they may come on gradually. How they develop is mostly dependent on the primary cause of the nerve compression. For example, RTS will often occur as a result of some acute injury where there has been a fracture or dislocation of the elbow joint causing a change in positional alignment of the bones in the elbow. In this case a rapid onset of symptoms could be directly related to the traumatic injury in the region.

In other cases the symptoms may arise more gradually. For example, when RTS is caused by tumors or tendinous bands in the nearby muscles, symptoms may occur more gradually. Repetitive activities involving supination and pronation of the forearm, especially when done from a position of elbow extension which stretches the nerve, are most likely to produce these symptoms.2

ASSESSMENT

Several pain and symptom patterns that help in recognizing RTS have already been introduced. In addition, pain from RTS is likely to be aggravated with activities like handwriting that cause prolonged isometric muscle contractions in any of the forearm muscles. The pain sensations are also likely to be reproduced with palpation directly on the supinator muscle distal to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. If fibers of the supinator muscle are compressing the posterior interosseous nerve, resisted supination of the forearm may also aggravate the symptoms.3

Weakness or palsy in the wrist and finger extensors is also a common finding. If the compression is only mild or moderate the client will often demonstrate an inability to extend the wrist or fingers against resistance because they will seem very weak. In addition to weakness, pain in the extensor muscles of the wrist may also be present with resisted wrist or finger extension.

TREATMENT

Massage and soft-tissue therapy can play a beneficial role in treating RTS. The practitioner should address other regions of potential nerve entrapment such as the thoracic outlet region, axilla, or lateral neck region in case there is a multiple nerve crush or neural tension problem in some other region that is aggravating the nerve compression symptoms of RTS.

Particular attention should be paid to the wrist and finger extensor muscles in the forearm. Deep longitudinal stripping techniques on these muscles will help free any neural restrictions in the distal region of the radial nerve. Decreasing tension in the wrist extensor muscles may also reduce the symptoms. Deep broadening techniques for the wrist extensors will also be of benefit in this region.

Methods of reducing nerve compression in the interface between the posterior interosseous nerve and the radial tunnel will be helpful. Firm pressure on the proximal region of the supinator muscle while the forearm is being pronated will help encourage elongation in the supinator muscle and may reduce compression on the nerve. However, the practitioner should be careful not to aggravate the symptoms by putting additional pressure on the compressed nerve.

Watch for the symptoms of RTS if a suspected lateral epicondylitis problem is not resolving. Deep friction massage over the lateral epicondyle region is the primary treatment for epicondylitis, and this treatment could aggravate an existing radial nerve compression. Therefore, if a deep friction treatment near the epicondyle aggravates neurological symptoms or pain farther down in the forearm, it is wise to consider the possibility of radial nerve entrapment in this region and modify your treatment approach accordingly.

While radial tunnel syndrome is not a commonly occurring condition, it can certainly be a painful and debilitating problem, especially if it is not adequately recognized. Because its symptoms are so often mistaken for lateral epicondylitis it is wise to have a clear understanding of both problems in order to provide the most effective treatment for lateral elbow and forearm pain.

References

- Dawson D, Hallett M, Wilbourn A. Entrapment Neuropathies. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999.

- Roquelaure Y, Raimbeau G, Dano C, et al. Occupational risk factors for radial tunnel syndrome in industrial workers. Scand J Work Env Heal. 2000;26(6):507-513.

- Moradi A, Ebrahimzadeh MH, Jupiter JB. Radial Tunnel Syndrome, Diagnostic and Treatment Dilemma. Arch bone Jt Surg. 2015;3(3):156-162.