The Double Crush

- Whitney Lowe

Orthopedic injuries to the nervous system are one of the more complex areas to understand. The nervous system is so pervasive throughout our body that there is hardly any tissue that is not affected by it in some way or another. While certain peripheral nerve conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome get a great deal of attention, there are other aspects to peripheral neuropathy that often get overlooked. The double (or multiple) crush phenomenon is one such consideration. In order to understand how it works let’s look at some basics of nerve physiology first.

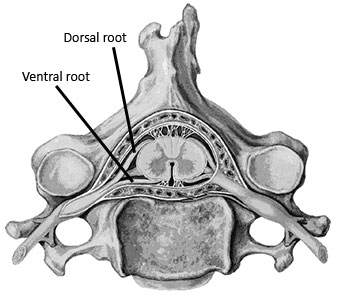

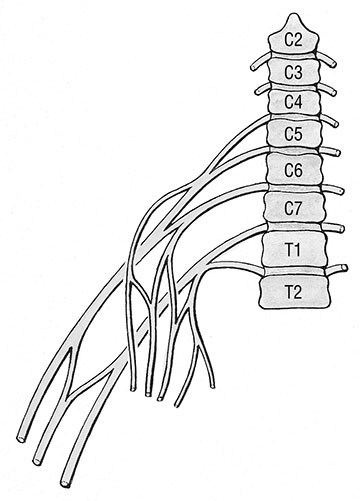

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate some basics of nerve anatomy. The section of the nerve that is closest to the spinal cord is called the nerve root. There is a dorsal root, which contains the sensory fibers going into the spinal cord, and a ventral root, which contains the motor fibers that are leaving the spinal cord. The sensory and motor roots then combine together to become the nerve trunk. These trunks are often grouped together as they leave the spinal cord in a similar area. When several nerve trunks are bundled together they make up a plexus. An example is the brachial plexus. A plexus often has a number of connections between the various trunks (Figure 2).

As the nerve trunks leave the plexus they begin to separate. They separate into distinct nerves that supply different regions of the extremities. Each of these separate nerves is called a peripheral nerve. If pressure is placed on a nerve root, by a herniated disc for example, the nerve compression problem is called a radiculopathy. When pressure is placed on the nerve farther along its path, as on the peripheral nerve, it is called a peripheral neuropathy. Sometimes compression placed on a nerve trunk where it is still part of a plexus may be called a plexopathy.

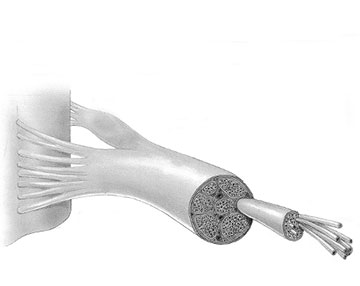

Once nerves exit the spinal cord they are surrounded by several connective tissue layers. A connective tissue layer called the endoneurium surrounds each individual nerve fiber. The nerve fibers are collected into bundles called fasicles that are surrounded by another connective tissue layer called the perineurium. Numerous bundles of fasicles then make up a peripheral nerve, which is enclosed within another connective tissue layer called the epineurium (Figure 3). It is important to have an understanding of these different layers of neural connective tissue because they play an important role in nerve-tissue pathologies.

The connective tissue layers are mostly for support and protection. However, some nerves have more support and protection from the connective tissue layers than others. For example, spinal nerves have either a poorly developed epineurium or may be devoid of it altogether. The lack of a solid epineurium makes the spinal nerves more susceptible to compression trauma and may be one explanation for the frequency of lesions to the nerve roots in the spinal canal.

In addition to the connective tissue layers and nerve fibers contained within a peripheral nerve, there is an intricate vascular supply to each nerve as well. The vascular supply is a complex web of tiny vessels within the nerve because the nerve needs adequate vascular supply to function properly. Ischemia (lack of blood flow) due to compression is likely to cause neurological symptoms and plays a role in the double crush syndrome.

The connective tissue layers also function as a tube for the transmission of cellular fluids. The nerve carries its own nutrient supply that is necessary for proper function. The nutrients are moved along through the nerve by a slow-flowing cytoplasm within the nerve cell called axoplasm. The flow of axoplasm inside the nerve fiber is called the axoplasmic flow. The axoplasmic flow goes in both proximal and distal directions. If there is a disturbance to this flow the individual is likely to experience various neurological symptoms such as pain, paresthesia, numbness, or motor impairment.

In the early 1970’s as diagnostic technology was improving, researchers were noticing that nerve compression problems were often occurring in more than one place at the same time. This phenomenon was first identified with the occurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients that also had lesions in the cervical region, and was labeled as the double crush phenomenon.

The double crush happens because a blockage in axoplasmic flow in one region may impair the function of tissues in distant regions of the nerve. For example, if a person has a proximal compression on the brachial plexus, everything distal to that site is more susceptible to pathology because there is a blockage in the axoplasmic flow and therefore a deprivation of nutritional supply to the nerve tissues. This is a likely reason why many clients have simultaneous symptoms of thoracic outlet and carpal tunnel syndromes.

While this condition is often called the double crush phenomenon (or syndrome), there may be more than two sites of compression on the nerve. In this case the problem would be considered a multiple crush. For example, if an individual has a protruding disc in the cervical region that is pressing on nerve roots of the brachial plexus, distal entrapment neuropathies such as carpal tunnel syndrome or pronator teres syndrome are more likely to occur.

It is important to realize that the double crush phenomenon does not increase the degree of compression on nerves in distant regions. What it does is increase the sensitivity of the nerves to compression or tension in distant regions. Since this has been acknowledged there has been recent discussion of other factors that may play a role in double crush phenomenon.

For example, there is a strong indication that metabolic factors that irritate nerves, as found in patients with diabetes, may contribute to the double crush phenomenon. The National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (http://www.niddk.nih.gov/index.htm) states several factors that may promote diabetic neuropathy (neurological symptoms that often occur with diabetes). These factors include:

- metabolic factors, such as high blood glucose, long duration of diabetes, possibly low levels of insulin, and abnormal blood fat levels

- neurovascular factors, leading to damage to the blood vessels that carry oxygen and nutrients to the nerves

- autoimmune factors that cause inflammation in nerves

- mechanical injury to nerves, such as carpal tunnel syndrome

- inherited traits that increase susceptibility to nerve disease

- lifestyle factors such as smoking or alcohol use

What is evident from this list is that there is likely to be an interaction between various metabolic disturbances and the onset of peripheral nerve pathologies. The practitioner who is looking for causes of peripheral nerve irritation should therefore look past just mechanical compromise (compression or tension) in the nerve fibers and consider the possibility of metabolic factors in the nerve as well. This is particularly true if the symptoms appear to be affecting more than one nerve.

For example, if the symptoms of nerve compression are felt only in the distribution of the ulnar nerve in the hand (Figure 4), it may be more likely that the problem is of mechanical origin in the nerve and may involve compression of the ulnar nerve in a peripheral region like the cubital tunnel at the elbow or Guyon’s tunnel in the wrist. If, however, the symptoms are being felt in the entire forearm and hand, it is more likely that more than one nerve is being affected and this could indicate a systemic disorder such as a metabolic disturbance.

The massage practitioner is faced with the task of identifying the cause of various symptoms in order to determine if massage is a proper treatment and, if so, what type of massage will be helpful. Nerve pathologies can be particularly challenging to identify. Failure to recognize the double crush phenomenon is one reason that many people do not get adequate treatment for various peripheral neuropathies. If there is a double (or multiple) crush phenomenon present, the practitioner needs to identify and treat all the possible regions of nerve impairment with whatever means will be most helpful. Failure to do this could result in frequent recurrence of the problem.